An article, "US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion worries TTOs", appears in the August issue of the subscription-only journal Technology Transfer Tactics. It discusses the US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion in June in Quanta Computers, Inc. v LG Electronics, Inc. The court ruled, in essence, that the application of the doctrine of patent exhaustion meant that LG could not control the downstream use of technology that it had licensed to Intel. That technology was used in Intel chips that were later sold to Quanta and other computer manufacturers. The decision means that LG cannot seek royalty payments from Quanta or other computer makers that purchased components produced by Intel under its licensing agreement with LG. Experts agree that this decision, while not in fact earth-shattering, underscores the need for strategic thinking when formulating licensing strategy and deciding how to implement it.

An article, "US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion worries TTOs", appears in the August issue of the subscription-only journal Technology Transfer Tactics. It discusses the US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion in June in Quanta Computers, Inc. v LG Electronics, Inc. The court ruled, in essence, that the application of the doctrine of patent exhaustion meant that LG could not control the downstream use of technology that it had licensed to Intel. That technology was used in Intel chips that were later sold to Quanta and other computer manufacturers. The decision means that LG cannot seek royalty payments from Quanta or other computer makers that purchased components produced by Intel under its licensing agreement with LG. Experts agree that this decision, while not in fact earth-shattering, underscores the need for strategic thinking when formulating licensing strategy and deciding how to implement it.

Sunday, August 31, 2008

US Supreme Court ruling on exhaustion worries lots of people

An article, "US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion worries TTOs", appears in the August issue of the subscription-only journal Technology Transfer Tactics. It discusses the US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion in June in Quanta Computers, Inc. v LG Electronics, Inc. The court ruled, in essence, that the application of the doctrine of patent exhaustion meant that LG could not control the downstream use of technology that it had licensed to Intel. That technology was used in Intel chips that were later sold to Quanta and other computer manufacturers. The decision means that LG cannot seek royalty payments from Quanta or other computer makers that purchased components produced by Intel under its licensing agreement with LG. Experts agree that this decision, while not in fact earth-shattering, underscores the need for strategic thinking when formulating licensing strategy and deciding how to implement it.

An article, "US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion worries TTOs", appears in the August issue of the subscription-only journal Technology Transfer Tactics. It discusses the US Supreme Court decision on patent exhaustion in June in Quanta Computers, Inc. v LG Electronics, Inc. The court ruled, in essence, that the application of the doctrine of patent exhaustion meant that LG could not control the downstream use of technology that it had licensed to Intel. That technology was used in Intel chips that were later sold to Quanta and other computer manufacturers. The decision means that LG cannot seek royalty payments from Quanta or other computer makers that purchased components produced by Intel under its licensing agreement with LG. Experts agree that this decision, while not in fact earth-shattering, underscores the need for strategic thinking when formulating licensing strategy and deciding how to implement it.

Friday, August 29, 2008

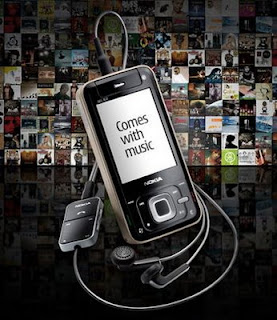

"Comes with music" and other experiments

A good article in the Irish Independent by Stephen Foley reflects the tensions that underpin the relations between the music performing/recording industries on the one hand and DRM-based music delivery systems such as iTunes on the other. While there is plenty of money in the iTunes business model, the intriguing questions remain (i) whose money ultimately is it and (ii) how can recording companies claw themselves back into the market for the delivery of albums now that iTunes accounts for more than two-thirds of all paid-for downloads. In this context Foley asks: "what is the point of the iTunes store if music is free?" The point is that, between file-sharing, promotional offers and Radiohead-style business models (see earlier IP Finance post here) the means of accessing music for free keep increasing -- which makes it difficult for anyone to compete with a paid-for product. For this reason

A good article in the Irish Independent by Stephen Foley reflects the tensions that underpin the relations between the music performing/recording industries on the one hand and DRM-based music delivery systems such as iTunes on the other. While there is plenty of money in the iTunes business model, the intriguing questions remain (i) whose money ultimately is it and (ii) how can recording companies claw themselves back into the market for the delivery of albums now that iTunes accounts for more than two-thirds of all paid-for downloads. In this context Foley asks: "what is the point of the iTunes store if music is free?" The point is that, between file-sharing, promotional offers and Radiohead-style business models (see earlier IP Finance post here) the means of accessing music for free keep increasing -- which makes it difficult for anyone to compete with a paid-for product. For this reason "The value of music sales in the US and Western Europe at the start of the decade was well over $20bn a year, almost all from CDs. In 2008, that will be down to $13.1bn, of which digital music accounts for $2.7bn. In short, revenues from paid-for downloads and online subscription services are not coming close to making up for the decline in CD sales. And Screen Digest predicts they never will. The market in 2012 will be $11.6bn, it calculates, with just $4.6bn from digital sales".Foley then cites the forthcoming Nokia "Comes With Music" initiative, which will launch before Christmas, selling phones-cum-music players that allow users to download and keep an unlimited amount of music. Universal and Sony BMG are said to be enthusiastically backing the service. Other experimental products are in the pipeline; for example, three of the four major labels are said to have signed up to support a new service by MySpace which will stream music for free on artists' pages on the social networking site, in return for sharing advertising revenues.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

OPEN SOURCE: WHO IS MAKING MONEY?

Since Red Hat is widely identified with the business side of the open source world, let's begin with it. The good news is that Red Hat saw a 32% increase in quarterly sales for the most recent period, to $157 million dollars. That translates into a 7% increase in profits. So why the bearish position of Wall Street analysts about Red Hat? According to the article, the bears on the Street continue to express concern about the slowing growth rate of the company.

At least two major reasons are cited for this sluggish growth. First, companies like Red Hat are more tech-support companies rather than purveyors of must-have technology. Second, brand awareness of their products remains low, apparently even so for a company supposedly as well-known as Red Hat.

So is anyone making out like a bandit in the open source space? Surprisingly perhaps, the article suggests that the winners are the traditional high tech goliaths--such as IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Oracle and Intel. Their success is based on taking advantage of the desire of companies to make increasingly lavish (and free) use of open source products by selling these companies complementary hardware, databases and consulting services to the open source products.

For instance, IBM sells billions (yes, billions) of dollars of hardware, middleware and services that are connected with open source programs. Oracle, the database giant, has made Linux a lucrative platform for its products. And the list goes on.

The bottom line here is the painful truism that, for open-source companies, just because their products enjoy large markets does not not mean they are currently enjoying commensurately large commercial success. Linux is free, IBM software is not. Guess who wins commercially, at least for the present. Investors and Wall Street are paying careful notice.

Cost-based valuation: is it a live issue?

An article by Simon Rowell, "Understanding Intellectual Property Value", was published earlier this month on IPFrontline.com. Reviewing IP methodology valuations, it inevitably discusses the cost-based, market-based and income-based techniques. On the cost-based methodology it says this:

An article by Simon Rowell, "Understanding Intellectual Property Value", was published earlier this month on IPFrontline.com. Reviewing IP methodology valuations, it inevitably discusses the cost-based, market-based and income-based techniques. On the cost-based methodology it says this: All of this is fine. But now here comes my confession of ignorance. I have never, in my admittedly limited and subjective personal experience, seen a live example of the cost approach that has ever been used for anything to do with IP rights. Does anyone in fact use it? Or does it only exist in articles and talks on IP valuation as an example of something that isn't much use?"... This method looks at the historical cost incurred to develop and create the intellectual property. ...

There are many inherent problems with the cost approach. The most significant is that it fails to reflect the earnings potential of the intellectual property. The value of intellectual property is derived from its earning potential, and not its cost. ...If the intellectual property offers significant economic advantage in an active market, the use of the cost method is likely to understate its value. If, on the other hand, development has been inefficient or lengthy, the use of the cost method might overstate its value. Also, for many identifiable intangible assets, it may not be possible to develop a replacement, or it may not be possible to estimate the replacement cost.

In its favour, the cost approach is useful as a readily calculated bottom-line valuation".

If readers can enlighten me, perhaps referring me to examples of active use of the cost-based approach, I'd be very grateful. If it seems that no-one does use it, can we make all articles and talks on IP valuation one paragraph shorter by dropping it?

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Illegality doesn't prevent franchisor recovering sums owed under a contract

In short, franchisor Master of Education sued Ketchell, the franchisee, before a local court in order to recover for money due under a franchise agreement. Ketchell claimed that since Master of Education failed to comply with clause 11 of the Australian Franchising Code, the franchise contract became unenforceable for statutory illegality. At trial the court concluded that, while Master of Education did not comply with the Code, its failure to do so did not render the receipt of the non-refundable payment illegal.

The New South Wales Court of Appeal concluded that the franchise agreement was effectively prohibited by the law; accordingly Master of Education could not recover the moneys claimed. The High Court has since unanimously upheld Master of Education's appeal, much to the great relief, presumably, of many a worried franchisor.

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Effect of merger on IP licensees in the US: where state law can't be ignored

"Despite a long history of case law relating to mergers, one area remains unclear, especially in the entertainment industry: the effect of mergers on intellectual property (“IP”) licensing agreements. Recent case law contributes to this uncertainty and suggests that certain precautions may be necessary to preserve valuable IP licensing rights".As usual -- and it seems remarkable that this warning should still need to be given -- the reader is reminded of the need for foresight [ie why not think about the risks/benefits of possible mergers before the licence is signed?] and vigilance [ie keep an eye on what goes on after the licence is signed]. The authors then focus on an annoying problem for those of us who like our licence provisions cut-and-dried, or at least predictable in terms of their outcome and effect. They explain:

"... the practice of having contracts transfer as a matter of law, even if prohibited by the express terms of the contracts without consent, may no longer be reliable in the context of transferring IP content and licenses.In one 2004 decision-- Evolution, Inc. v Prime Rate Premium Finance Corp., Inc., 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25017 (D. Kan. 2004) -- a court has concluded that “whether a merger effectuates an automatic assignment or transfer of license rights is a matter of state law.” But other recent federal court decisions have held that the licensing agreement, rather than the applicable state merger statute, determines whether the licence can be transferred to the surviving company without the consent of the licensor. Thus unless the licence agreement clearly permits assignment of the IP rights without the licensor's consent, that licensor may well be able to challenge the right of a surviving company in a merger to operate as the licensee -- even though state merger law transfers all the rights under the licence as a matter of law.

While the impact of a merger on the assets of the parties to the merger is governed by state law, IP licenses are also governed by a body of statutory and judicial federal law. More recent case law points to a trend of IP law starting to impact how traditional state merger laws treat IP rights as different than that of other assets. However, the trend is neither uniform nor consistent".

Reading this article, I found myself wondering about the extent to which a prudent licensee -- or anyone seeking to buy his business -- should make an effort to obtain advice concerning the operation of state law as well as federal law, factoring this advice into the structuring of its business transactions.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Sources of Olympic Revenue

With the conclusion of the Beijing pyrotechnics, both on and off the field of competition, it is worth considering the breakdown in the sources of revenue for the Olympic Games. Based on figures provided to Business Week by the International Olympic Committee, as reported in the August 11 issue of that magazine, the projected revenue sources were as follows:

With the conclusion of the Beijing pyrotechnics, both on and off the field of competition, it is worth considering the breakdown in the sources of revenue for the Olympic Games. Based on figures provided to Business Week by the International Olympic Committee, as reported in the August 11 issue of that magazine, the projected revenue sources were as follows:Broadcast rights 50%Based on estimated revenues of $3 billion, that means that some some undefined portion of $60,000,000 (I hope that I have my math right!) in revenues can be attributed to sales of licensed products in connection with the two-week event. Being a licensing person at heart, the disproportion between the amount of revenues due to sponsorships and licensing is striking indeed.

Sponsorship 40%

Ticketing 8%

Other (including licensing) 2%

This disproportionality is especially noteworthy if the amount of the sponsorship revenues collected by the IOC will be compressed into a shortish period of time (If any readers have further information on this point, I would be delighted to be enlightened.) The $60,000,000 amount is a graphic reminder that it takes a lot of sales of licensed items to reach substantial royalty aggregates. That said, it will be fascinating to see how many post-event Olympic items will be sold, and what is the ultimate ratio between the sponsorship and licensing revenues.