"The patent world is undergoing a change of seismic proportions. A small number of entities have been quietly amassing vast treasuries of patents. These are not the typical patent trolls that we have come to expect. Rather, these entities have investors such as Apple, Google, Microsoft, Sony, the World Bank, and non-profit institutions. The largest and most secretive of these has accumulated a staggering 30,000-60,000 patents.Slightly mischievously, I did a word count on "Intellectual Ventures" which revealed 279 references to that remarkable business. Even more mischievously I did a word-count for "Europe", which secured just three mentions. This is an absorbing, well-reasoned and attractively-presented essay -- but it cries out for a counterpart based on European data, regulatory mechanisms and legal background with which to complement it. Is there anyone in Europe who is prepared to take up this task?

Investing thousands of hours of research and using publicly available sources, we have pieced together a detailed picture of these giants and their activities. We consider first the potential positive effects, including facilitating appropriate rewards for forgotten inventors, creating a market to connect innovators with those who can manufacture their inventions, and most important, operating as a form of insurance – something akin to an Anti-Troll defence fund.We turn next to the potential harmful economic effects, including operating as a tax on current production and facilitating horizontal collusion as well as single firm anticompetitive gamesmanship that can raise a rival’s costs. Most important, we note that mass aggregation may not be an activity that society wants to encourage, given that the successful aggregator is likely to be the one that frightens the greatest number of companies in the most terrifying way.

We argue that mass aggregators have created a new market for monetization of patents. It is vast, rapidly growing, and largely unregulated. We conclude with some normative recommendations, including that proper monitoring and regulation will require a shift in the definition of markets as well as a different view of corporations and their agents".

Monday, January 30, 2012

The giants among us -- or US"?

"The Giants Among Us" is an article by Tom Ewing & Robin Feldman that has recently been published at 2012 Stanford Technology Law Journal 1. You can read it online here. Astonishingly, given that it was posted three weeks ago and covers such an important subject, no readers' comments have yet been posted in response to it. IP Finance readers may wish to take note of its abstract:

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Marks and Brands in the Auto Industry II: Motorsport

It can be argued that the most valuable IP of a motorsport team is its brand: it is by allowing third parties to associate themselves – through sponsorship -- with their brand that teams earn much of their money. Similarly, it can be argued that technical IP serves merely to enhance the value of the brand by facilitating race success.

It can be argued that the most valuable IP of a motorsport team is its brand: it is by allowing third parties to associate themselves – through sponsorship -- with their brand that teams earn much of their money. Similarly, it can be argued that technical IP serves merely to enhance the value of the brand by facilitating race success.Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise to learn that a “green” vehicle design company Set up in 2007 by Gordon Murray, former Technical Director of the successful McLaren and Brabham motorsport teams, has 13 different trade mark registrations compared with 9 patent families and two design registrations. The company also maintains a high public profile, its most recent press release announcing the development of a new electric-powered sports car, the Teewave.

In this latter respect, Gordon Murray Design seems similar to the electric sports car manufacturer TESLA founded by another high-profile figure, Elon Musk, co-founder of PayPal. Financial commentators blow hot and cold on TESLA’s prospects: it will be interesting to see how Gordon Murray Design fares.

In this latter respect, Gordon Murray Design seems similar to the electric sports car manufacturer TESLA founded by another high-profile figure, Elon Musk, co-founder of PayPal. Financial commentators blow hot and cold on TESLA’s prospects: it will be interesting to see how Gordon Murray Design fares.More analysis of the IP business models of Gordon Murray Design and two other “green” UK automotive companies is available here.

Loss Leaders and Bait and Switch: Marks and Brands in the Auto Industry

I have always thought that when a car company advertises a certain model, the primary intention is to sell as many units of that model as possible. It had never occurred to me that a given model might be promoted for marketing purposes other than the goal of necessarily selling that model. "Loss leaders"?-- that is for the local pharmacy; "bait and switch"--that is for the local supermarket. Surely neither of these marketing ploys could have any relevance for the marketing and promotion of an automobile brand.My, oh my -- was I wrong!

I have always thought that when a car company advertises a certain model, the primary intention is to sell as many units of that model as possible. It had never occurred to me that a given model might be promoted for marketing purposes other than the goal of necessarily selling that model. "Loss leaders"?-- that is for the local pharmacy; "bait and switch"--that is for the local supermarket. Surely neither of these marketing ploys could have any relevance for the marketing and promotion of an automobile brand.My, oh my -- was I wrong!Consider the following two items that appeared in separate December 2011 issues of The Economist. In the first article ("Difference Engine: Volt farce") here, which appeared in the 8 December issue, the focus is on the challenge facing GM in dealing with questions over the safety of the electric battery, the technological centerpiece of the highly touted Volt electric car here.

Against that background, the article stated as follows:

"For General Motors, a good deal of the company’s recovery from its brush with bankruptcy is riding on the Chevrolet Volt (Opel or Vauxhall Ampera in Europe), its plug-in hybrid electric vehicle launched a year ago. Not that GM expects the sleek four-seater to be a cash cow. Indeed, the car company loses money on every one it makes. But the $41,000 (before tax breaks) Chevy Volt is a “halo” car designed to show the world what GM is capable of, and to lure customers into dealers’ showrooms—to marvel at the vehicle’s ingenious technology and its fuel economy of 60 miles per gallon (3.9litres/100km)—and then to drive off in one or other of GM’s bread-and-butter models."Stated otherwise, the "Volt" brand is being promoted no less for the broader message that the brand is intended to convey about the technological capabilities of a reborn General Motors than for the the direct sales potential of the model (at least for the foreseeable future, which remains uncertain). While the Volt is not exactly a loss-leader, I am sure that GM wants to make a lot of money on this vehicle, if for no other reason than the costs of bringing a new car model to market. Still, the current tribulations of the Volt car point to the fact that GE cannot really allow customer perception of the vehicle as a symbol of the company's technological prowess, even if the model itself is not directly contributing to the company's bottom line.

But this is hardly the first time that an automobile model has been used to serve purposes other than the direct sale of the model in question. This was brought home in the article in the 17/24 December issue of the same magazine ("Retail Therapy: How Ernest Dichter, an acolyte of Sigmund Freund, revolutionised marketing") here. Dichter, while today largely forgotten, was a seminal figure in the marketing revolution that took place in the 1930s and 1940s, where the focus was how to exploit irrational purchasing behaviour for better sales performance. Dichter was a committed student of Freud, and his focus was on the Freudian preoccupations of the day, emphasizing the emotional, the irrational and the sexual.

In this context, perhaps Dichter's most creative marketing ploy was his approach to the then new line of Plymouth cars. The problem was that sales of the Plymouth brand were lagging. Dichter reasoned that the problem could be found in the slogan--""different from any other one you have ever tried." Dichter reasoned that the slogan triggered an unconscious fear of the unknown in purchasers. The solution that he fashioned was ingenious. Dichter gleaned from interviews that, while only 2% of car purchasers (in 1939) owned a convertible, they (especially middle-aged men) almost all dreamed of owning one.

And so the ploy. The male would be drawn into the showroom to look at the convertible--a symbol of "youth, freedom and the secret wish for a mistress". He would then return with his wife, who had no interest in sharing her husband with a mistress, even of the four-wheeled variety. The compromise was the purchase of a sensible sedan -- of the Plymouth variety of course. It was a clever scheme to leverage one model to encourage the purchase of another.

It would be overstated to suggest that the Volt is a "loss leader" in the traditional sense, or that the Plymouth convertible was a "bait and switch" tactic. Still, there are tantalizing points of similarity. In the auto industry as well,the interrelationship among the mark, the brand and the product are at once both more and less than that which meets the eye.

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

Institute for Capitalising on Creativity wants knowledge transfer associate

|

| St Andrews: a leading institution in the fields of innovation, creativity and saving energy by not turning on the lights when it gets dark ... |

The position is based in Edinburgh and candidates are invited to apply if their backgrounds are in economics, management or law. The deadline for applications is 15 February and you can get more information here.

Monday, January 23, 2012

IP Valuation: a good introduction

Since by no means all of the readers of this weblog also follow the IPKat, I thought it advisable to draw the attention of readers to this piece by Dr Nicola Searle which was posted on the IPKat this afternoon on IP valuation. Dr Searle's article, replete with links to basic concepts, some leading thinkers and their works, provides a good introduction to the topic for those who are not yet familiar with it.

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Australia: new register affects security interests in IP

The most recent Arthur Allens Robinson IP Focus is on "IP and the transition to the Personal Property Securities Act". According to its authors (Tim Golder, Tom Reid and Geoff McGrath), companies and individuals that own, license or hold security interests in intellectual property should be aware that the Personal Property Securities Register (the 'PPS Register') will go live on 30 January 2012, ushering in the reforms implemented by the Personal Property Securities Act 2009. This focus looks at the transitional arrangements and the implications of the new regime.

The most recent Arthur Allens Robinson IP Focus is on "IP and the transition to the Personal Property Securities Act". According to its authors (Tim Golder, Tom Reid and Geoff McGrath), companies and individuals that own, license or hold security interests in intellectual property should be aware that the Personal Property Securities Register (the 'PPS Register') will go live on 30 January 2012, ushering in the reforms implemented by the Personal Property Securities Act 2009. This focus looks at the transitional arrangements and the implications of the new regime. IP owners and their advisers should be aware that security interests over intellectual property which have already been registered with IP Australia (the Australian patent and trade mark office) will not be automatically migrated to the PPS Register and will need to be re-registered. During a 24-month transitional period, pre-existing security interests will continue to be protected -- even if they have not yet been registered on the PPS Register. Once that period ends, owners of pre-existing security interests that have not been registered will risk losing priority.

IP owners and their advisers should be aware that security interests over intellectual property which have already been registered with IP Australia (the Australian patent and trade mark office) will not be automatically migrated to the PPS Register and will need to be re-registered. During a 24-month transitional period, pre-existing security interests will continue to be protected -- even if they have not yet been registered on the PPS Register. Once that period ends, owners of pre-existing security interests that have not been registered will risk losing priority.Thanks are due to Robyn Chatwood (Slaughter and May) for drawing my attention to this item.

Thursday, January 19, 2012

A uniform transaction tax regime for the EU?

1709 Blog reader John Walker posted the following question as a comment on that blog, but it seems to me that it's more likely to receive an answer on this one. He writes:

"Australia used to have a very complex sales tax regime (for example the tax on tissue paper in a box was much more than the tax on the same tissue paper if wrapped around a toilet roll). Australia in the year 2000 introduced a uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST). GST largely replaced a complex and hard to see system, levied by both the Federal and the individual state governments, with a uniform tax levied at the same rate on every transaction. (there are some exceptions, but nobody's perfect)Can any reader give John some assistance on this point?

Many of the EU's copyright' levies are transaction taxes; the nexus between the consent of a right holder and payment to the same right holder is clearly severed.

Doesn't the EU have any policy about aiming for a reasonably uniform transaction tax regime?"

"You'll never walk alone" -- in adidas boots, at any rate

|

| "You'll neeeee-veeer waaalk alone": the Anfield anthem |

A new six-year sponsorship agreement has been struck with a US business which has very little profile in the UK, Warrier, the sum in question being said to be in the region of £150 million. Warrior is owned by New Balance.

This blogger can see why adidas is reluctant to pay to back a loser, though the supply of teams that are generally winners is very small -- a pool that is considerably smaller than the number of potential sponsors. What will be interesting to discover is the overall impact on adidas of the adverse publicity surrounding the termination of its relationship with Liverpool. The club's supporters are famed for their fervent passion, their extraordinary loyalty and their long memories, and they may not appreciate their team being spoken of in such irreverent terms.

Thursday, January 12, 2012

IP and Stock Market Returns

Deleting a bunch of (unread) emails a few days ago, this author spotted one with the contents of the Summer Edition of the MIT Sloan Management Review. An article on "The Business Models that Investors Prefer" by Weill et al attracted his attention. It's abstract suggested an overview of new research which indicating that the stock market valued business models based on innovation and intellectual property.

Deleting a bunch of (unread) emails a few days ago, this author spotted one with the contents of the Summer Edition of the MIT Sloan Management Review. An article on "The Business Models that Investors Prefer" by Weill et al attracted his attention. It's abstract suggested an overview of new research which indicating that the stock market valued business models based on innovation and intellectual property. The authors (and more than twenty of their students) have taken the time and trouble to classify the business models used by 10,000+ publicly quoted companies on US stock exchanges into several categories. They identified four assets types (financial, physical, intangible (our friend!) and human, as well as four ways in which companies exploiting these assets (creators, distributors, landlords and brokers). The revenues were then allocated among each of these categories. As the authors explained, this allows companies with similar business models to be compared as well as seeing trends in the data. The data extends beyond the 2008 Global Financial Crisis into 2009.

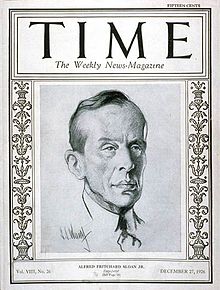

Alfred Sloan - invested heavily in

Automobile Innovation

Intriguingly 81% of total revenue still comes from physical assets, according to their work and manufacturing generated 57% of all company revenues. This seems to this author to be counter-intuitive to the frequently heard statement that physical assets are becoming less important in the US economy. On the other hand, the revenues recorded are presumably the world-wide revenues for US companies whose manufacturing units may be based in South-East Asia. Investors rated these companies highly. Financial assets performed badly - not surprising when one considers that the data encompassed the meltdown of the financial companies.

Most intriguing was the observation that so-called IP landlords had the second best stock market performance. These are companies that use licenses or subscriptions to sell rights to use their intellectual property. The examples quoted are the New York Times and Microsoft. The best perfumers were innovative manufacturers who are presumably also massively exploiting their own intellectual property.

It's the first study that I've seen which has tried to go beyond using patent data as a proxy for innovative activity. Patents are really only good at measuring technical innovation. The likes of Disney or the New York Times have few - if any - patents but are clearly innovative in exploiting their intellectual property (more copyright and brand-related issues).

The authors demonstrate clearly that investors like innovative manufacturing business models. There is a question left unanswered by the paper: do investors prefer innovative manufacturing and/or IP landlord business model because they produce better returns on the investment - or is there a herd instinct here? Are investors piling into such companies because their contemporaries are doing the same. What is ultimately better economically?

Technorati Tags:

Investor, Stock Market, Intellectual Property

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

In the mood for a webbie and a bit of INTIPSA?

Mike Sharpe (Chief Operating Officer, INTIPSA -- the International Intellectual Property Strategists Association) has let it be known that the organisation is hosting a webinar on Tuesday 17 January, entitled "Brands, Tax and Finance". He promises:

If any reader of this weblog is signed up for the webinar, will he or she please report back on the most exciting and/or useful bits. And can that person let know whether "brands", in this context, only means consumer brands, or whether those unfashionable things, business-to-business brands, have any significance in this context ...

"We’ll be discussing IP tax regimes, transfer pricing and the IP issues around offshoring of brands. Panellists: Steef Huibregtse of Transfer Pricing Associates, Anne Fairpo of Atlas Chambers [and the IP Finance weblog] and Serena Tierney, former Head of IP at O2, Telefónica, Disney and Diageo [though not all at the same time ...]".Registration and further details are available on INTIPSA's website here.

If any reader of this weblog is signed up for the webinar, will he or she please report back on the most exciting and/or useful bits. And can that person let know whether "brands", in this context, only means consumer brands, or whether those unfashionable things, business-to-business brands, have any significance in this context ...

Friday, January 6, 2012

Is There "Gaming" of the Patent System?

I think that the first time that I heard the reference to "gaming the system" in the context of intellectual property was in a class lecture given by a friend and colleague. The course, one of the few of its type offered by a top-tier MBA program, sought to impart to its students an appreciation of the way by which a proper understanding of IP could be of service as part of a manager's s professional skill set. I was sitting in on the class to gain a better appreciation about how to pedagogically approach MBA students. I don't remember too much about the actual contents of the lecture (it was, after all, a few years ago). What I do recall well was one sentence which he reiterated several times in response to various suggestions by students how to exploit the patent system. My friend said loud and clear--"Don't try to game the system"!

What exactly did he mean? He did not elaborate, at least not in the class session that I attended that day. Ever since that I encounter, I have sought to try and work it my mind what the term might mean in the IP context.

Let's start with a definition, taken from, where "gaming the system" is acting so as

That sounds pretty negative to me. The trouble is that I continue to have difficulty in articulating the difference between making use of patent rules and procedures for one's benefit, while maintaining the integrity of the system, as opposed to nefariously manipulating the system in a way that, while it might be work to my advantage, also does harm to the patent system itself. It is assumed that "gaming the system" does not mean that one is breaking the law, but merely that one's conduct somehow works to the detriment of the system even if it allows one to achieve his desired goal. Stated in that way, however, I still struggle to find a reasoned way to distinguish between conduct that does, and does not, "game the patent system." Let me suggest several examples:

1. Submarine patents-- Prior to legislative amendments in the 1990s, it was possible under U.S. patent law to engage in what was called "submarine patenting." As the U.S. Committee on the Judiciary noted in a 2008 report,

2. Patent trolls--It is well-known that certain companies and law firms pursue patent litigation on the basis of a granted patent for which the patentee is not making any use thereof. Loud voices were raised about such conduct amounting to a perversion of the patent system. Whether or not public criticism was a factor, it remains that the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C here, limited the ability of a plaintiff to use the patent system to extract a monetary settlement in circumstances where there was not exploitation of the patent by the patentee. Neither the navigator of the submarine patent or the alleged patent troll was said to have broken any law, but merely to have adroitly exploited it for his ultimate monetary benefit.

In both instances, the legal system ultimately took steps to rectify what was perceived an unacceptable exploitation of the patent system. On that basis, both submarine patenting and patent trolling could be seen as instances in which the conduct of the patentee was not in the best interests of the patent system, even if such conduct worked to the patentee's benefit. Circling back, however, to the beginning of this blog post: is the role of the manager to refrain from either submarine patenting or patent trolling because it does not serve the best interests of the patent system? If the answer is "yes", then there are potentially huge implications for how we conceive of the role manager in respect of IP rights in particular, and all legal rights, more generally. If the answer is "no", then I remain with the question: what do we mean by "gaming" the patent system?

What exactly did he mean? He did not elaborate, at least not in the class session that I attended that day. Ever since that I encounter, I have sought to try and work it my mind what the term might mean in the IP context.

Let's start with a definition, taken from

"[t]o use the rules and procedures meant to protect a system in order to instead manipulate the system for a desired outcome."

1. Submarine patents-- Prior to legislative amendments in the 1990s, it was possible under U.S. patent law to engage in what was called "submarine patenting." As the U.S. Committee on the Judiciary noted in a 2008 report,

"[p]rior to requiring the publication of [U.S. patent] applications, the public would not learn of a patent until after it issued, which is often several years after the application was filed. Some patentees took advantage of this practice to the extreme (with ‘‘submarine’’ patents), and intentionally delayed their patents issuance, and thus publication, of the patent for several years to allow potentially infringing industries to develop and expand, having no way to learn of the pending application."The law was changed to prevent submarine patenting, at least with respect to U.S. applications for which there were also foreign parallel applications. The question is: was "submarine patenting" an example of "gaming the system"? On the one hand, the lack of disclosure until a later time potentially put third parties at risk that they were be the object of an infringement action without having prior reasonable knowledge of the existence of the invention. On the other hand, it still seems to be the case that can engage in such conduct provided he limits himself to a U.S. patent application. Is this "gaming the system" or simply calculated use of patent rules and regulations?

2. Patent trolls--It is well-known that certain companies and law firms pursue patent litigation on the basis of a granted patent for which the patentee is not making any use thereof. Loud voices were raised about such conduct amounting to a perversion of the patent system. Whether or not public criticism was a factor, it remains that the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C here, limited the ability of a plaintiff to use the patent system to extract a monetary settlement in circumstances where there was not exploitation of the patent by the patentee. Neither the navigator of the submarine patent or the alleged patent troll was said to have broken any law, but merely to have adroitly exploited it for his ultimate monetary benefit.

In both instances, the legal system ultimately took steps to rectify what was perceived an unacceptable exploitation of the patent system. On that basis, both submarine patenting and patent trolling could be seen as instances in which the conduct of the patentee was not in the best interests of the patent system, even if such conduct worked to the patentee's benefit. Circling back, however, to the beginning of this blog post: is the role of the manager to refrain from either submarine patenting or patent trolling because it does not serve the best interests of the patent system? If the answer is "yes", then there are potentially huge implications for how we conceive of the role manager in respect of IP rights in particular, and all legal rights, more generally. If the answer is "no", then I remain with the question: what do we mean by "gaming" the patent system?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)